Multiple Choice Hinge Questions

- Adam Kohlbeck

- Jul 8, 2025

- 4 min read

Multiple-choice questions generally evoke a mixed range of responses from teachers and school leaders whenever they are used in a lesson or as a teacher’s attempt to gauge understanding.

The argument against focuses on the fact that pupils could theoretically mask a lack of understanding with a lucky guess. Alternatively, they could use logic and the process of elimination to determine what the answer must be without understanding why it is so. However, a carefully crafted multiple choice question – one that is well placed within the learning sequence and has well-designed deliberate distractors – can be of undoubted value to teachers.

When should you ask multiple-choice hinge question?

While they could be used literally anywhere in a sequence of lessons, they have particular use at the point in the sequence where crucial differences are being drawn between previously known knowledge and new content, or to distinguish between two concepts that are closely related but subtly different.

This is exemplified excellently by Daisy Christodoulou (2013) in her blog post, which you can access here. She gives the example of the question: How did the Soviet totalitarian system under Stalin differ from that of Hitler and Mussolini? There are clear similarities between the systems imposed by all three dictators, and all three come under the heading of dictatorships, which could indicate to pupils that they are all the same. This would represent a fundamentally underdeveloped understanding, and so it is crucial that, before moving on to more complex content, the teacher knows which pupils hold this underdeveloped understanding. This is where the term ‘hinge’ comes in. Evidence Based Education describes a hinge point as being the point in a lesson or sequence where the teacher must decide whether to move on or go back over content. A hinge question, therefore, provides the teacher with the necessary information to make this decision.

How should you ask one?

Hinge questions when asked to the whole class, can be useful. For example, a teacher may ask,

“How should I decide which fraction out of two presented to me is greater?”

This would elicit an explanation of the process, during the course of which, pupils would reveal their understanding, or lack thereof, of the concept at hand. However, this style of hinge questions is problematic because of the time it would take the teacher to hear from every pupil before deciding whether to move on or reteach. The other obvious issue is that pupils could copy the response of others.

A method for quickly assessing what all pupils appear to know and understand is useful for teachers. To achieve this, teachers could provide an example of a question to test out pupil understanding and then assess responses on mini whiteboards. For example, Which is greater? 2/3 or 2/5. Answers to this question will give the teacher some useful information, but not all of the information that they need. The fractions both have the same numerator which means that pupils only have to know that the larger denominator will indicate the smaller fraction.

To improve the question, we should include options that are less obviously different. William, (2015) citing Vinner, (1997), offered these two contrasting examples and indicated how success rates can fluctuate considerably when plausible alternatives to the correct answer are offered.

Use Plausible Detractors

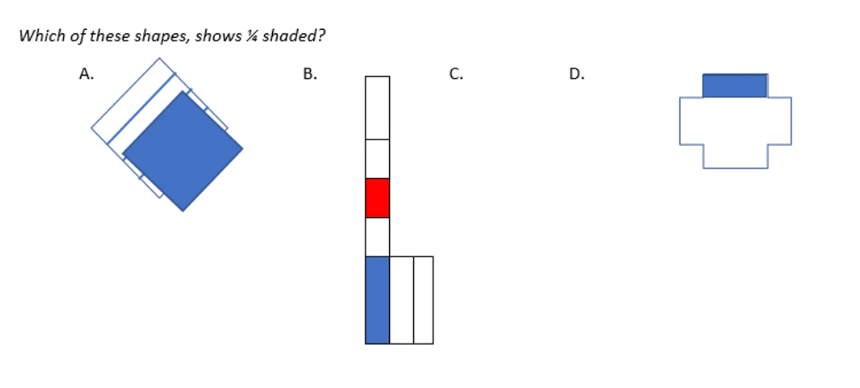

Sherrington and Stafford (n.d.) wrote, ‘The most effective hinge questions go beyond simple recall, combining concepts and challenging students to apply ideas.’ Part of applying ideas is the potential to misapply them, and in so doing, expose a misconception. Therefore, when utilising multiple choice as the question style at hinge moments in learning sequences, teachers should ensure that they build in what Sherrington and Stafford go on to refer to as ‘Plausible detractors’. These are possible answers that appear to be potentially correct. Even more effectively, teachers could choose to include detractors that expose precise misconceptions that they want to pre-empt because they know from past experience (or the advice of more experienced colleagues) that they are particularly common. For example, consider the options provided for the question below:

Option A is the correct answer but let us imagine a pupil who does not nominate any of the options. This would indicate a misconception about fractions of uncommonly seen shapes. If option B were selected, this would indicate a misconception about the need to have equal parts in any fraction. Option C would indicate a misconception about the role of the denominator, and option D would suggest a misconception around the complete area of the shape needing to be divided into 4 rather than the identification of 4 equal parts within a greater whole.

Making the most of Multiple Choice Hinge Questions

While multiple-choice questions designed with little thought and planning are unlikely to provide teachers with any useful information, by choosing the right moment— the hinge moment — in the learning sequence and by designing multiple-choice questions that reveal pupil understanding, we can increase the value of the data they give. To supercharge our use of multiple-choice hinge questions, teachers should pay careful attention to selecting plausible detractors as incorrect answers. Doing so will reveal vital insights about specific misconceptions held by pupils and tell teachers whether it is time to move on or recap.

References

Christodoulou, D. (2013, October 30). Research on Multiple choice questions. Daisy Christodoulou. https://daisychristodoulou.com/2013/10/closed-questions-and-higher-order-thinking/

Evidence Based Education (n.d.). Assessment and feedback in an online context: Hinge questions. Chartered College of teaching. https://my.chartered.college/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/EBE3‑1.pdf

Sherrington, T. and Stafford, S. (n.d.). Catch out misconceptions with multiple-choice hinge questions. Impact. https://my.chartered.college/research-hub/catch-out-misconceptions-with-multiple-choice-hinge-questions/

Wiliam D (2015) Designing great hinge questions. Educational Leadership: Journal of the Department of Supervision and Curriculum Development 73: 40 – 44.

.png)

Comments